Ahmed Shah built the Karachi Arts Council into a cultural powerhouse — now he’s dreaming of what comes next

To passersby on the long, narrow stretch of M.R. Kyani Road in Saddar Town, the Arts Council of Pakistan Karachi (ACPK) is an imposing highbrow institution — a place of grand auditoriums, performing arts and cultural conferences, whose preference for intelligentsia fodder (ie plays of classic literature and modern satire) is often advertised by the giant banners at its grilled iron gate.

These posters may both wow and alienate most people of the city — sometimes in the same breath. However, if one were to walk inside and see past the elitist appearance of culture, one would see what the ACPK President, Ahmed Shah, whose services to the arts have been acknowledged by the Sitara-i-Imtiaz and Hilal-i-Imtiaz, has accomplished.

In its present state, ACPK is not just a place for the select nobs, toffs and the swells of the city. It is a place for everybody, if they truly love the arts, that is. In the last decade, it has become difficult to separate the man, Ahmed Shah, from the institution, and vice versa. Together, the two form a singular power brand that serves as the patron of the arts for not just Sindh, but all of Pakistan.

But it wasn’t like that 25 years ago. Two and a half decades ago, ACPK, a non-governmental organisation whose origins date back to 1948 as an arts and cultural society, lay in tatters and ruin. Its buildings needed more than brick and mortar patchwork, and the halls craved cultural excitement.

Cautious of religious extremism, barely surviving on crumbs, and led into further despair by mismanagement, this public institution needed an exit from the era of cheap “stage shows” that sullied the name of comedy (read bargain-basement variety) that ran amok and fouled up most of the city’s cultural activities. By today’s comparison, the works that meant something more than entertainment — that were both serious and satirical, helmed or authored by names synonymous with literature and culture — were far fewer in number.

The ACPK auditorium was practically unused. The first change of breeze came when Shah offered it nearly free of charge as a venue for the 3rd KaraFilm Festival in 2003. The Karachi International Film Festival revamped the auditorium, sound and lights and even brought a new energy to the surrounding grounds. It drew massive crowds, often visiting the ACPK for the first time. The Festival would continue to use the ACPK till 2009. It would change the whole look of the ACPK as it existed then and establish it as a nerve centre of youthful cultural activity.

But the quiet revolution took its sweet time, play by play, activity by activity, election by election. Today, ACPK stands tall as the hub of cultural variety and a place to learn, hone, explore, profit from, and showcase the arts.

A man of culture

In his office (with walls lined with works of art by masters), Ahmed Shah tells Icon that what we see — and have yet to see — had always been his dream.

“I made these plans years ago, but making them a reality took years of patience and diligent, non-stop work,” he explains. Realising dreams requires energy, and Shah admits he has more of it than people half, or even a quarter, his age.

“[Most of the motivation stems from] my own satisfaction,” he says. “That’s what keeps me going. If you’re not working for your own contentment, if you’re not striving to dream better dreams, then you’ll lose energy. And when the dream becomes a reality, you start dreaming new ones. I’m 66 years young now, but the dreams haven’t stopped.”

Shah, in his own words, was once an angry, dissatisfied young man who was enamoured by the arts, but questioned its distance from the masses. When he started work at the Arts Council of Pakistan Karachi, more than two decades ago, people didn’t even have chairs to sit on, he remembers.

“Everything I did was deliberate,” Shah says, explaining the origins of his resolve to swim against the tide. “Back when I was still studying, I used to sit among progressive intellectuals, philosophers, psychologists — people such as Raees Amrohvi, Saleem Ahmed, Shaukat Siddiqui, Syed Muhammad Taqi and Qamar Jamil, among others. It was a different world altogether. I could’ve taken the easier route by becoming a doctor, engineer, chartered accountant or bureaucrat, but I chose otherwise. In a city such as Karachi, where institutions are few and one’s identity is often reduced to and defined only by one’s appearances, I knew I had to think differently.”

When Shah speaks, he imparts decades of his own learning experience for the benefit of the listener: the conversation is never in the tone of a know-it-all, or one-sided. When he speaks of culture — the backbone of our conversation — he doesn’t use the word lightly. “Culture isn’t static,” he says with the quiet conviction of someone who has spent a lifetime watching it morph, expand, get commodified, and occasionally rescued from oblivion.

“It’s not confined to just the arts or a painting on a wall,” he says, pointing to the works of art in his office. “It evolves constantly, much like the mobile phone in your pocket.” Shah’s analogy is more than fitting.

“Where once a fixed landline in the drawing room was the symbol of communication, the modern cell phone now opens access to global content, OTT platforms, and the very nerves of international culture. This access shapes our cultural identity, while also allowing external cultures to seep into our own,” he notes. “Culture is, at its core, a way of life. It is deeply personal yet shaped by collective experience.”

Ahmed Shah understands that culture is not merely folklore, literature or classical music. Instead, he sees culture as a constantly shifting landscape. It is influenced by religion, language, geography, clothing, and even by where one lives: whether it be a rural area or a bustling urban block.

“As Faiz Ahmed Faiz mentioned in his lectures that have been compiled in book form,” he adds, matter-of-factly (the book, one gathers from the way he speaks, should be available at the bookstore in the premises), “religion plays a central role in defining culture. Our prayers, our festivals — whether held in masjids, churches, pagodas or mandirs — all speak to that connection.” The diversity of cultural expression, he believes, is rooted in people’s daily lives, and the interplay between these layers, between the old and the new, is where culture truly comes alive.

Speaking about global cultural shifts, Shah draws a vivid image from history: the rugged clothes worn by dock workers at the Port of Marseille — and the jeans we wear today — were born out of necessity. Those early forms of jeans now find their way into high fashion, even worn by presidents of powerful nations. That’s how culture evolves, he says.

“Globalisation and industrialisation change and impact everything from fashion to thought.”

But amid this change, he warns, not all aspects of culture get preserved. “The culture of the elites — the hukmaraan [ruling] class — that’s what survives, and that influence dominates, adapts and dictates the times.”

The Mughals, he reminds me, adopted Farsi (Persian) as the language of power. Then came Urdu and, later, English, and thousands of words filtered into our vernacular. “So, if we want to preserve indigenous culture, we must first stop thinking of it as stagnant. Preservation does not mean halting evolution.”

Patronage of the arts

That evolution includes Gen-Z — a generation that Shah does not belittle. Shah explains that the way to ACPK’s future is the youth. This, however, is not a talking point from an electoral speech. Shah doesn’t judge the youth for their way of thinking, he accepts them just as they are.

“They’re creating new sensibilities, new expressions. Our job is to give them space — but never at the cost of tradition,” he says.

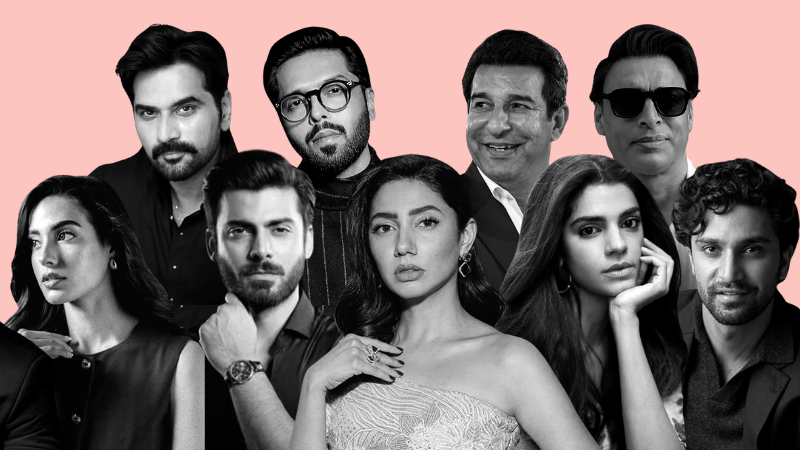

ACPK has expanded not just in infrastructure but in imagination as well. Classical music, experimental theatre, improv comedy and literature all find a home under its roof, he adds — but that’s not all. New additions to ACPK’s catalogue of initiatives include fashion design and film, for which Shah is creating education programmes.

The lack of widespread, affordable education of these art forms, and the non-existence of platforms or institutions to support and showcase emerging talent in both the fashion sphere and the film industry, has pushed both fashion and film to the point of near-extinction, he laments.

Shah also points out that film is the medium where all art forms meet. Its power as a cultural export cannot be dismissed or diminished. However, cinema culture won’t be born in the posh localities of DHA Phase VIII, he affirms — it needs grassroots vision, and institutions that understand and support the endeavour.

Shah says that the ACPK’s doors — its auditoriums, studios, sound stages, technical facilities — are open to anyone with a creative tilt: both youngsters and experienced professionals are welcome. And there’s more.

The young people who wish to shoot films or shorts, or want to set up fashion runway events, will be supported by mind-boggling discounts, Shah says, adding that he may even support them free-of-charge if the cause is absolutely genuine.

Television drama productions, corporates and commercial endeavours, on the other hand, have to pay the going rate, which, he adds, is still quite low when compared to rental costs of commercial studios and sound stages. The Arts Council, he adds, takes money from these corporations and puts it to good use: the money is diverted to support the young. “We don’t sell culture or the youth — we reinvest in it,” he affirms.

Still, the lack of funds and infrastructure remains a concern. “We need upgrades. More galleries, libraries, audio-visual studios, and classrooms. I have built them when I could, where I could, but that is not enough [for a city as big as Karachi].”

At this point, I ask Shah about how Arts Councils across Pakistan work, whether there is government support for such establishments, and why ACPK seems to be the most proactive of all cultural institutions.

“Every Arts Council in Pakistan is structured differently,” he explains. “The Lahore Arts Council and Alhamra are government-run. Ours, here in Karachi, and others in Sindh, such as Larkana, Khairpur, Sukkur, Nawabshah [Shaheed Benazirabad] and Mirpurkhas, function independently and are registered as NGOs [non-governmental organisations]. We operate democratically, as elections are held every two years. Whoever is elected must generate ideas and activities, and not just occupy the seat.”

Continuing, he doesn’t shy away from criticism of the broader system. “Many institutions that fall under the government operate without passion — even if there are passionate people in them, the system robs them of independence and freedom,” he says.

“For most of them, it’s just a job. No vision, no ideas. Boards are filled with big names, but they have no financial independence. They receive funding but can’t spend it the way they need to. It’s not any secretary’s or minister’s fault,” he sighs with a slight shrug of his shoulders.

Often a part of most think-tanks and initiatives from the federal and provincial governments in Sindh, Punjab and Islamabad, Shah says the problem lies in “systemic inertia.” “No one takes, or is allowed the will to take, initiatives.”

Shah says this unjumpable hurdle is a colonial remnant. “From the time of the English, we’ve been taught censorship — this can happen, that cannot. Even Allama Iqbal’s poetry once needed a No Objection Certificate [NOC] from the Deputy Commissioner. Thankfully, that didn’t last.

“Our independence is our strength,” he adds, signalling again to ACPK’s origins as an NGO that is not dependent on, nor takes orders from the government. That’s not to say that everything goes when it comes to artistic expressions, he explains, in the tone of a teacher who can discern just how much a boundary can be pushed. ACPK self-censors, but without compromising the work’s intention and integrity.

“It’s not suppression,” Shah clarifies, “it’s roshan khayal [enlightened] thinking. We push boundaries without breaking what is essential [to our societal and cultural norms].”

The ‘big four’

The scale of ambitions at the ACPK is grand indeed. At the vanguard of its initiatives is the annual Aalmi Urdu Conference, now in its 17th year; the Pakistan Literature Festival; The Women’s Conference and the World Culture Festival — the ‘big four’ that realise Shah’s ambitions to make ACPK and its events into brands.

The World Culture Festival, launched last year, hosted over 450 participants from 44 countries; this year, that number of countries has ballooned to over 120, with perhaps a thousand or more visiting artists and technicians.

“Think of the logistics,” he enthusiastically says. “People from Jamaica, Comoros, the USA, Iran, Russia, Ukraine, Palestine, 31 African nations and 30 from Europe. We have nothing to do with international conflicts,” he adds, saying the event functions as a hub of cultural representation and exchange — a platform where everyone performs at the exact same stage, shoulder-to-shoulder, side-stepping conflict.

This global recognition hasn’t come without challenges. “We’ve faced threats [in the past and even now],” he admits. “But the Arts Council of Pakistan Karachi has become a name that carries weight. We’ve become internationally acknowledged, the ‘big news’,” he says proudly.

Ahmed Shah is adamant that culture is not the privilege of the affluent. “Most intellectuals — men and women of letters, professors, poets — they’re from the lower-middle class. The real ‘elites’ of society are not the financial elites, but intellectual ones.”

He recalls inviting Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi and Anwar Maqsood to the Arts Council. “Anwar Maqsood used to write only for TV. I brought him to the theatre,” he notes. Not only that, Shah brought in corporations and multinationals into the fold as patrons of the arts — a difficult job to accomplish, he admits. That interest opens doors for the young. “At the HBL gallery, [artist] Rashid Rana’s work is showcased alongside paintings by our fine arts students,” he says. “That is an achievement in itself.”

Alongside the rush of never-ending work, Shah is also quietly seeking a successor. “I won’t be here forever. The institution needs someone who shares the vision, not just a title,” he points out solemnly. Until then, he stands committed to extending support to every young artist and filmmaker, and emerging fashion designer, every voice that needs a platform — from gender rights forums to youth conferences.

“Culture is your identity. A society without culture,” he pauses, “is a dead society. Fashion design, communication design, film, theatre, visual arts — these aren’t luxuries, but signifiers of who we really are. Art moves, adapts, survives.”

And perhaps that’s the legacy Ahmed Shah hopes to leave behind: a culture that breathes. One that remembers its roots, welcomes the new, and belongs to everyone.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON, July 20th, 2025

Cover image by Tahir Jamal/Whitestar

Comments